Myths about Blondin

Unravelling the falsehoods from his 1860 biography

In 1860, just before his first English tour, Blondin released a promotional biography. From his birthplace to his family background and training, many of its claims have been repeated, but few stand up to scrutiny.

This page explores the falsehoods and fabrications in that booklet, and the reasons why they were, and continue to be, so widely accepted.

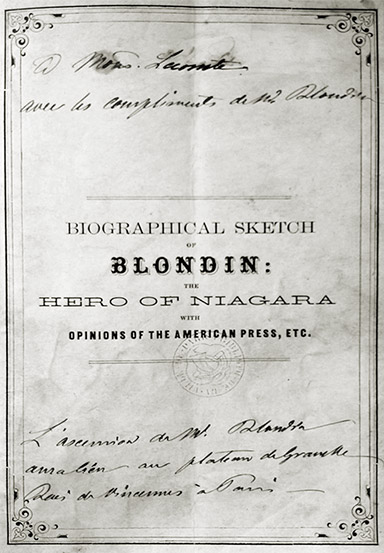

The 1860 Promotional Biography

The biography was produced under the supervision of Blondin’s manager, Harry Colcord, and printed in Buffalo, New York. It was dated October 24, 1860 and signed simply H.C. Although the booklet ran to 47 pages, only six were devoted to Blondin’s life story.

Several crates of the booklet were shipped to England ahead of Blondin’s first tour. Copies were widely distributed to journalists and the public. The aim was clear: to offer a ready-made version of his life story and discourage deeper investigation. For those who might have looked more closely, the facts were deliberately blurred.

A Hidden Life

Blondin’s 1860 booklet was less a celebration of his origins than a carefully crafted diversion. Unbeknown to most readers, he had already contracted a second marriage in New York while still legally bound in France. That act exposed him and Charlotte to prosecutions: bigamy, adultery and perjury in the United States, each carrying up to ten years imprisonment; a possible five year sentence in England; and as much as twenty years of forced labour back in France.

When his first wife died, Blondin married Charlotte again in London on 29 October 1881. To avoid scandal and a church ceremony, he registered himself falsely as a widower and Charlotte as a spinster—thereby committing forgery of a Register Office document punishable by up to seven years penal servitude and risking revocation of his British naturalisation. Charlotte too faced serious charges for aiding bigamy and forgery.

Blondin authorised the myths in that promotional biography, guiding early writers away from his French records. It was only after Jean-Louis Brenac discovered the Paris‑held original booklet and cross‑checked it with civil registers that the true story emerged. (Read more about Jean-Louis Brenac on Brenac’s Biography page.)

Some of the Myths and Misrepresentations

-

Myth: His name was Charles Blondin.

Fact: It is easy to believe this, since British newspapers of the 1850s and 1860s almost always called him Charles Blondin. In reality, he was born Jean François Gravelet and never used “Charles” in his own publicity or correspondence. The “Charles” was a creation of the English press, possibly to make his name sound more familiar to British readers, and the habit stuck in the United Kingdom. Elsewhere in the world, and in his own words, he was known simply as Blondin. Continuing to use “Charles” today repeats a historical inaccuracy.

-

Myth: The booklet exists simply to embellish Blondin’s early life.

Fact: It was a deliberate smokescreen to conceal a terrible secret: Blondin was a bigamist, facing prison and forced labour if exposed.

-

Myth: Blondin was born in Saint-Omer.

Fact: He was born in Hesdin, as confirmed by his birth certificate.

-

Myth: His father fought at Austerlitz and Wagram as a Napoleonic soldier.

Fact: He was a travelling acrobat between 1805 and 1809 and only possibly conscripted for the Russian campaign in 1812.

-

Myth: In 1824, his father was a weary ex-soldier.

Fact: That same year, he was still performing as an active rope dancer.

-

Myth: Blondin was trained at the Gymnasium School in Lyon.

Fact: He trained within his family troupe, who considered him too valuable to part with.

-

Myth: He was orphaned at the age of nine.

Fact: He was thirteen when his father died, and already performing with his family.

-

Myth: He emigrated to the United States in 1855.

Fact: He arrived in April 1851 with Gabriel Ravel.

-

Myth: He performed with the Ravel troupe for three years.

Fact: He remained with them for six years.

Behind the Legend

The falsehoods circulated in Blondin’s name were not merely the product of carelessness. They were part of a deliberate attempt to shape his image for the press and public. Yet the reality, pieced together from records and family history, is no less compelling.

These inventions offer a window into the workings of nineteenth-century publicity and the pressures faced by performers in the spotlight. For the full account of Blondin’s life, grounded in verified documents and research, see the Biography page.

Further Reading

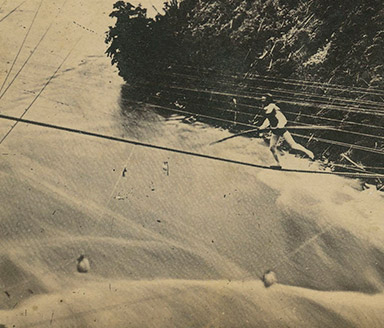

Blondin’s Feats

From his legendary crossings of Niagara Falls to theatre performances and royal invitations, this page showcases the variety and spectacle of Blondin’s career.

Explore the feats