Blondin's Feats

Enter a world of high-wire daring, theatrical spectacle, and breathless suspense

The rope is safe. I am safe. It is only the spectators who are in danger from fright.

Blondin, 1861

Across continents and decades, Blondin redefined what was possible on the high wire. His fame exploded in the summer of 1859 when he crossed the Niagara Gorge before tens of thousands of spectators. In the years that followed, he performed breathtaking stunts, from blindfolded crossings to chair balancing, on stages across the world, from London and Paris to Calcutta, Sydney, and New York.

Explore the fearless feats that made Blondin a legend.

Niagara: The Feats That Made Him Famous

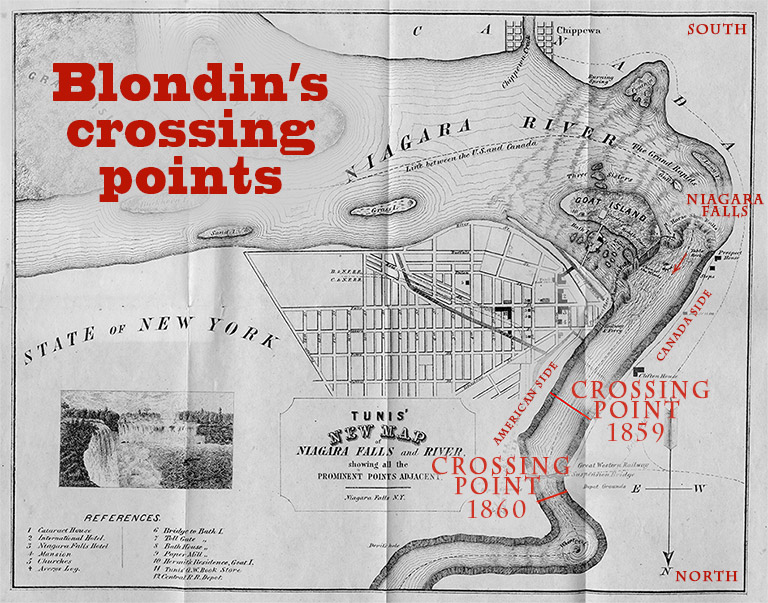

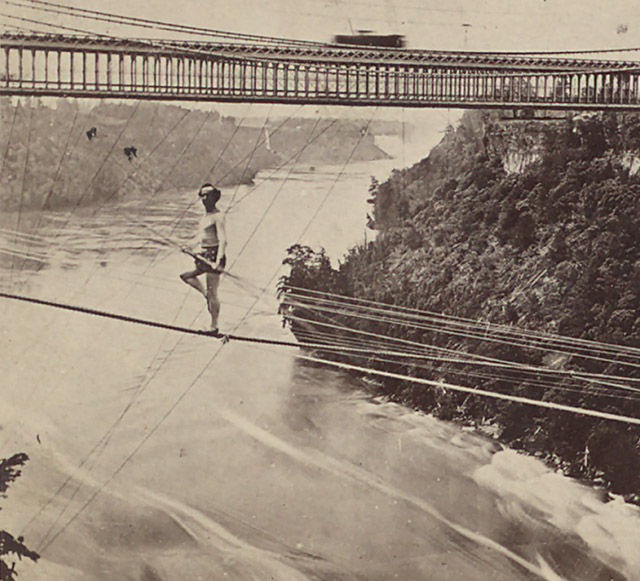

In 1859, Blondin transformed the tightrope into a stage of spectacle and danger. High above the Niagara River Gorge, between the United States and Canada, he astonished vast crowds with feats never before imagined, let alone attempted.

His first crossing, on 30 June, spanned 335 metres on a rope just 8 centimetres wide, suspended over the turbulent river. He walked confidently, paused midway, and lay down on the wire. The crowd of 25,000 erupted in cheers.

In the weeks that followed, he returned again and again, each time inventing new risks. He crossed blindfolded. He wore a sack over his body. He walked on stilts. Once, he carried a cooking stove and made an omelette on the wire.

Perhaps the most daring of all came on 19 August, when he carried his manager, Harry Colcord, across on his back.

Blondin returned the following year for a final series of Niagara performances, adding fireworks, animals, and ever more elaborate props. These crossings made him a sensation and set the tone for a lifetime of innovation.

Not a sound was heard but the rush of the waters below. The slightest false step would have been fatal, yet he moved as if on firm ground.

New York Times, 1859

A Repertoire of Risk

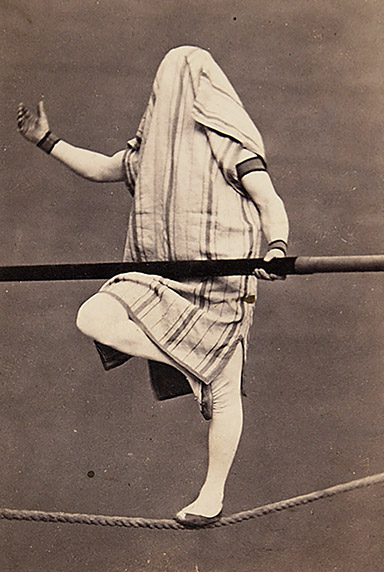

Blindfolded and Backwards

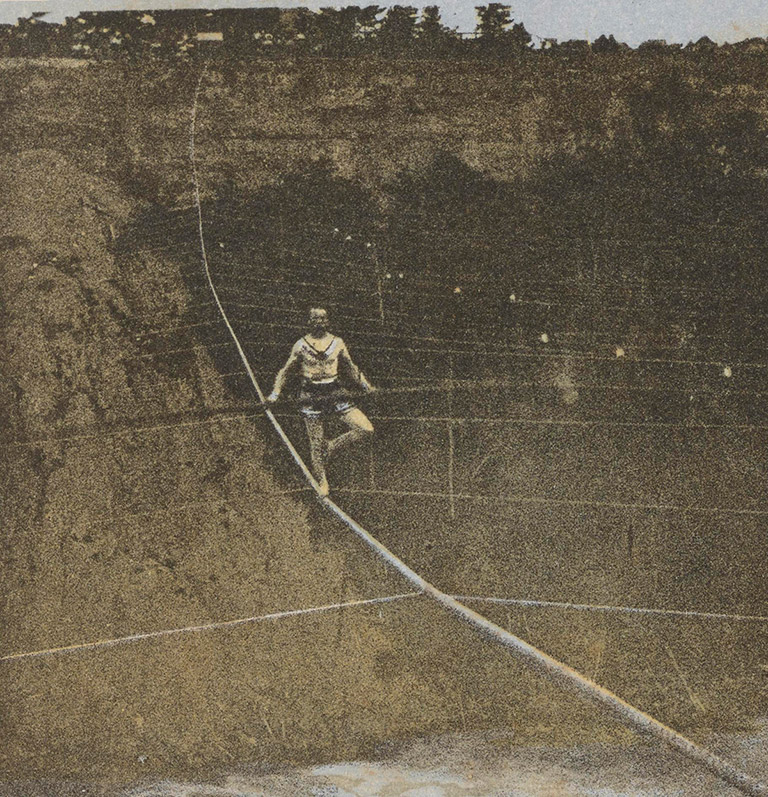

Among Blondin’s most unnerving displays were his blind crossings. Cloaked in a sack or masked by a blindfold, he stepped onto the wire without visual cues, relying solely on instinct and touch.

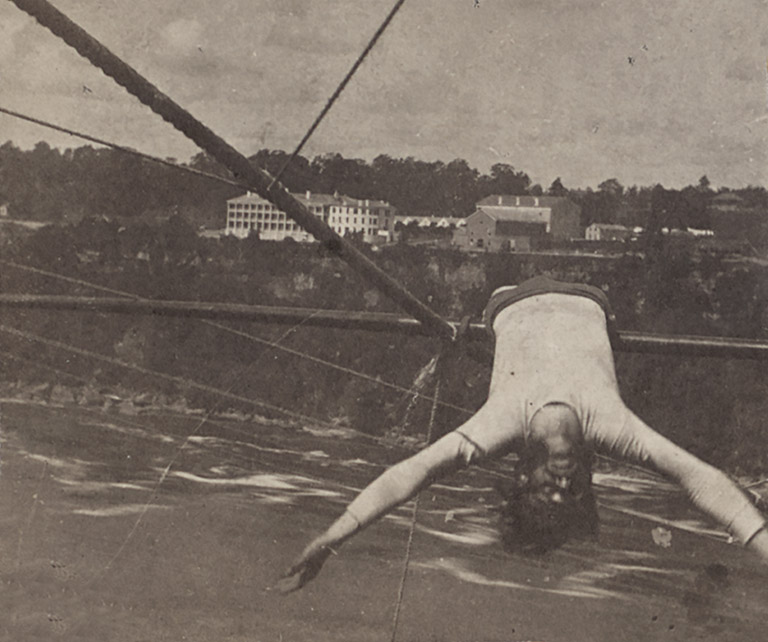

At times, he pushed the danger further still: pausing mid-air to lie down, balance on one foot, or even perform a handstand. These moments astonished audiences not just for their difficulty, but for what they revealed: a performer so attuned to the rope that he seemed to move by memory alone.

Carrying a Man

In one of his most extraordinary feats, Blondin carried a man across the wire on his back. First attempted at Niagara with his manager, Harry Colcord, the act was later repeated in other cities — but never lost its power to shock.

It came to symbolise the essence of Blondin’s appeal: total mastery, absolute nerve, and a calm defiance of what others deemed impossible.

Cooking on the Wire

In one surreal performance, Blondin paused mid-crossing with a 25-kilogram stove and cooked an omelette high above the river. The meal was lowered to passengers in a boat below.

The routine debuted at Niagara and was later adapted for crowds in Britain and Australia. As ever, it was not just the balance that astonished, but the absurdity of such calm domesticity suspended over a fatal drop.

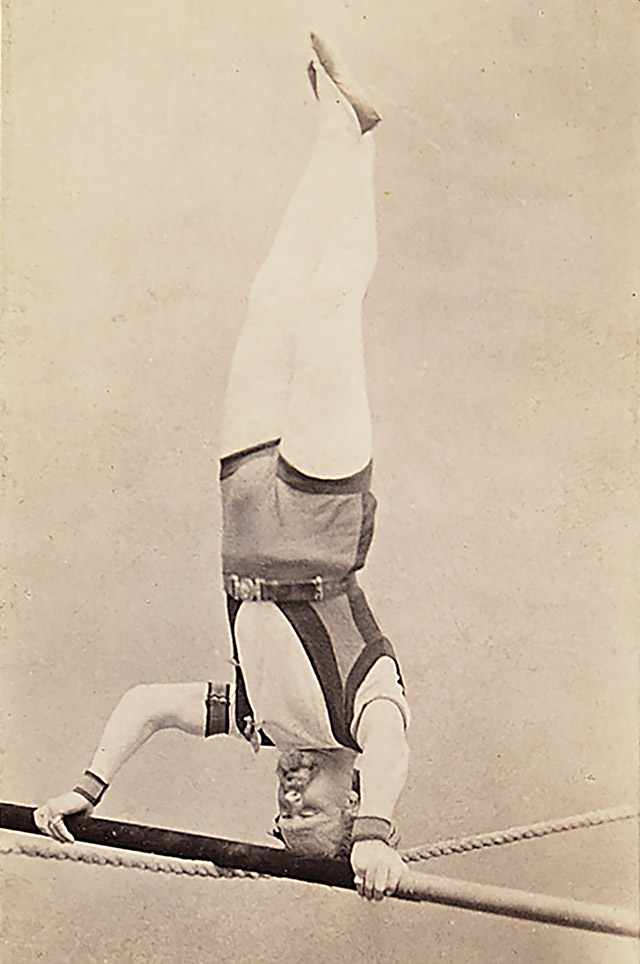

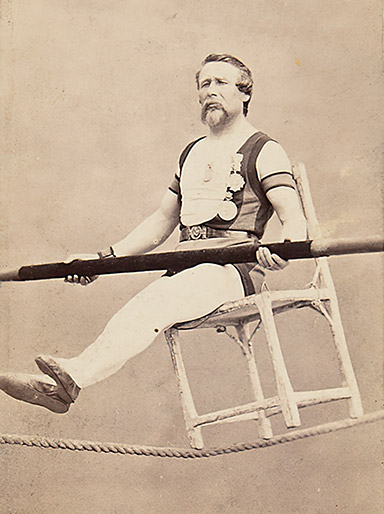

Chair Balances

Blondin would place a wooden chair on the rope, by two legs, then sit on it. In some versions, he stood on the backrest to perform slow, deliberate poses, steadying himself with a pole.

This feat was first performed over the Niagara Gorge in 1860, but it became a highlight of his act elsewhere too, from London’s Crystal Palace to theatres in Paris and Bordeaux. The danger was never staged: the chair was real, the risk was real. Blondin’s performances were theatrical but never faked. Every feat was genuine, performed without hidden supports or safety devices, the result of years of rigorous practice, physical control and calculated risk.

Bicycles, Beasts and Fireworks

Never content to repeat himself, Blondin found ever stranger ways to test the limits of balance. He rode a bicycle across the rope with characteristic ease, pausing partway to strike a pose or change direction.

In other performances, he led animals across: a dog, a monkey, even a lion cub. He sometimes performed at night, or amid fireworks, or in costume.

Every feat Blondin performed was underpinned by extraordinary physical discipline. He trained obsessively, not just to walk, but to leap, roll and recover on the rope with fluid precision.

Audiences saw him spin, twist, somersault, hang by one leg, straddle the rope, swing by his arms or with one hand, even rise from lying flat without using his hands. These flourishes were more than acrobatics, they were expressions of total mastery, honed over decades. Blondin did not merely walk the tightrope, he made it his stage.

His crossings at Niagara remain among the most iconic moments in the history of performance and adventure. But his legacy extends far beyond a single location. Across the world, from fairgrounds to theatres, his feats redefined what could be achieved with balance, daring and imagination.

To this day, Blondin continues to inspire performers, artists and risk takers. His life reminds us that the extraordinary is often just one step beyond the possible.

Further Reading

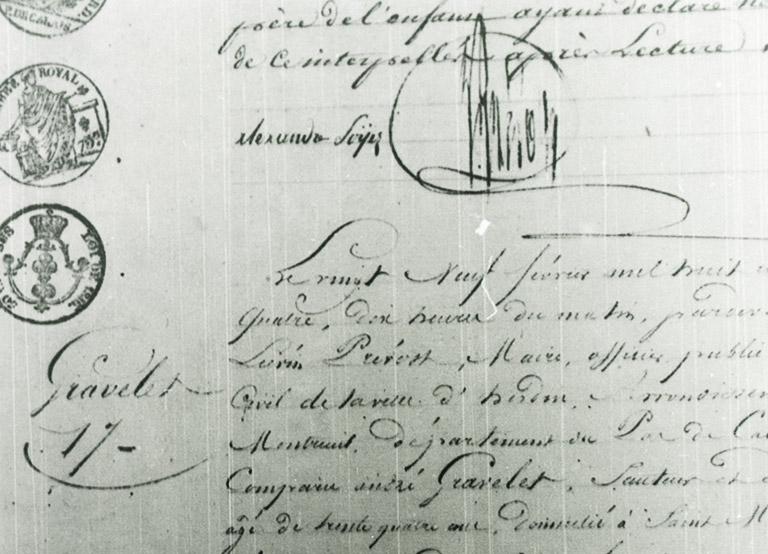

Traces of a Legend

Original documents & eyewitness accounts

Behind the feats lie the fragments: eyewitness accounts, original documents, and press reports that reveal how Blondin was seen in his own time.

Browse the Blondin Archive